Bronze-Age Britons, Iron-Age tribes and Romans all left their mark but it was under the Normans that the story of our market town began.Helen Morgan from Abergavenny Local History Society reports

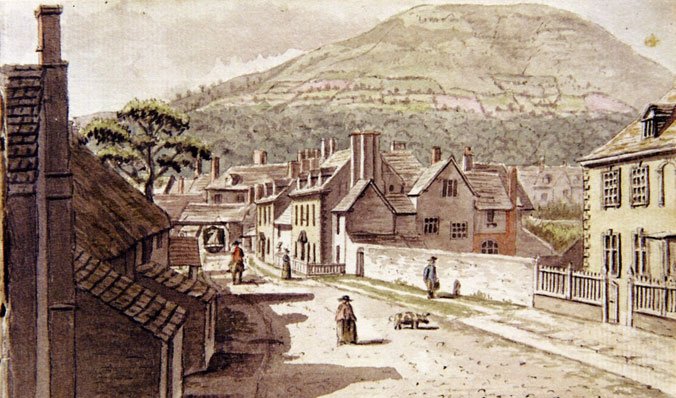

A watercolour of Monk Street in 1784 by Joshua Gosselin

The Christmas Day Massacre is Abergavenny castle’s badge of shame. In 1175, William de Braose, the Norman lord invited his long-standing Welsh rival Seisyll ap Dyfnwal and other Welsh noblemen to a Yuletide feast in the Great Hall, supposedly as a gesture of peace. As was customary, the Welsh left their arms at the door — whereupon the Normans slaughtered them all before capturing and killing Ap Dyfnwal’s wife and only son, Cadwaladr. The 12th century was undoubtedly a time of strife as local Welsh rulers feuded with the Norman invaders. But even by standards of the day, this was an atrocity that shocked Normans and Welsh alike. The murdered Welshmen’s kin eventually attacked the castle in 1182 seeking revenge but, sadly for them, de Braose himself was not at home. Only in 1233 was the entire wooden motte-and-bailey castle destroyed by Richard Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, and the Welsh princes. In the decades that followed, the castle was rebuilt — this time in stone, and the first town walls with four gates were erected — in Frogmore Street, Monk Street, Cross Street and Tudor Street.

The town grew and prospered during the Middle Ages. From the 13th century, two weekly markets were held and livestock was traded in nearby streets.

Abergavenny produced exceptionally fine flannel. Later it was home to a wig-making industry, using goats’ hair said to be bleached with a special recipe invented here. Mills along the Cibi brook below the castle established Mill Street as an industrial area in Tudor times, and it was here that the leather industry thrived until the late 19th century.

Owain Glyndŵr’s army attacked in 1404 and set fire to the churches, the tithe barn and houses but the town recovered. Henry VII’s victory at Bosworth in 1485 was widely celebrated and two years later his uncle, Jasper Tudor, became Lord of Abergavenny. Thanks, possibly, to the town’s royal connections, the Priory church that De Braose had endowed survived the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Instead, it replaced St John’s as the parish church with some of the priory’s income used to fund the King Henry VIII grammar school for boys in the old church.

During the Civil War, local gentry mostly sided with King Charles. As a result, Abergavenny castle was destroyed and left in ruins. The “Great and the Good”, however, largely adhered to their religion. Gunter House in Cross Street was home to a secret Catholic chapel until, abetted by the Titus Oates hysteria, its priests were arrested and executed. A decade later in 1688, the chief officers of the town refused to take the oath of allegiance to the Protestant William III and lost Abergavenny’s charter.

Improvement Commissioners were appointed to administer the town in 1794. They instructed John Nash to build a produce market on the site of today’s town hall, partly paved the streets and regulated overhanging buildings, but by the mid-19th century the town improvements had stalled. . Water and gas supplies were erratic. Sewage disposal was non-existent. Visitors praised the setting of the town but complained about its “straggling irregular” character and “ill-paved streets”. The population of 2,500 in 1801 had doubled by 1851 as the Industrial Revolution got underway. The canal had opened in 1812, the tramroad from Govilon Wharf to Llanfihangel built in 1814 was extended to Hereford by 1829, and the railway linking Hereford and Newport was nearly complete.

Then, in October 1853, a group of local tradesmen staged a civic coup during a meeting at the Angel Hotel. They took over the gasworks, installed street lighting, paved the streets, built the Llwyndu reservoir and organised collection of “night soil”. Two more train stations opened to service the line from Merthyr Tydfil to Abergavenny, known as the Heads of the Valley line. One at Brecon Road (now a surgery) had a ticket window inside the Station Hotel. The other was Junction Station by Ross Road where the Heads of the Valley line joined the Newport-Hereford line, and from where a spur ran to the lunatic asylum. Houses were built on the Grofield for the railway workers. Pubs sprang up to cater for them. The Union Junction between the Usk Bridge and Brecon Road housed and serviced more than 100 locomotives and their rolling stock. In its heyday, more than 1,000 people worked on the railways here. In the early days, leather goods, clothes, hats, candles and beer were manufactured in the town which also boasted a printer and iron foundry. A livestock market opened in 1863, replacing the sheep market in Castle Street. The present town hall and market hall followed in 1869-71 – statements of Victorian civic pride. }

Then, in October 1853, a group of local tradesmen staged a civic coup during a meeting at the Angel Hotel. They took over the gasworks, installed street lighting, paved the streets, built the Llwyndu reservoir and organised collection of “night soil”. Two more train stations opened to service the line from Merthyr Tydfil to Abergavenny, known as the Heads of the Valley line. One at Brecon Road (now a surgery) had a ticket window inside the Station Hotel. The other was Junction Station by Ross Road where the Heads of the Valley line joined the Newport-Hereford line, and from where a spur ran to the lunatic asylum. Houses were built on the Grofield for the railway workers. Pubs sprang up to cater for them. The Union Junction between the Usk Bridge and Brecon Road housed and serviced more than 100 locomotives and their rolling stock. In its heyday, more than 1,000 people worked on the railways here. In the early days, leather goods, clothes, hats, candles and beer were manufactured in the town which also boasted a printer and iron foundry. A livestock market opened in 1863, replacing the sheep market in Castle Street. The present town hall and market hall followed in 1869-71 – statements of Victorian civic pride. }

The early 20th century brought charabancs full of people wanting to spend their leisure time (and money) in a town of beauty and culture. Local eisteddfodau had been held here since 1834 and the first National Eisteddfod was held here in 1913.

The trains that had brought prosperity, however, had also brought cheaper goods from elsewhere to the detriment of local business. Bad weather and steep gradients forced the closure of the Heads of the Valley line in 1958, and the 1863 livestock market recently closed, too. Yet the market hall is still open for business and so, too, is the Castle.

The trains that had brought prosperity, however, had also brought cheaper goods from elsewhere to the detriment of local business. Bad weather and steep gradients forced the closure of the Heads of the Valley line in 1958, and the 1863 livestock market recently closed, too. Yet the market hall is still open for business and so, too, is the Castle.

The next history lecture in the Borough Theatre is on November 19 at 7.30pm when Martin Johnes will talk about Wales and the Christmas story. Non-members are welcome to join on the night. www.abergavennylocalhistorysociety.org.uk