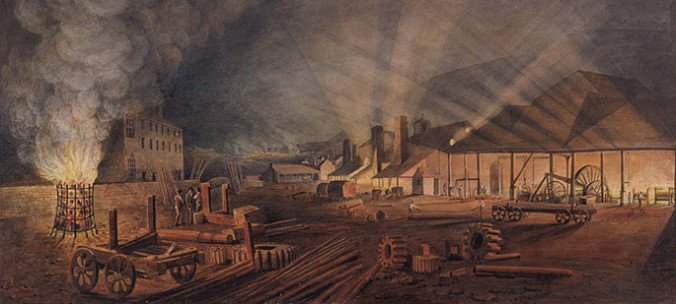

In the mid-18th century, a tiny hamlet in the hills became the heartbeat of the industrial revolution. Helen Morgan reports

It was the Seven Years’ War that did it. Demand grew for ships, cannon and other war machinery needed to support King George III’s colonial ambitions, and the price of iron soared.

Attention turned to the remote hills of south Wales, and by 1759 a group of English entrepreneurs had realised that the top of the Taff valley was blessed with a magic mix of iron ore plus plentiful timber and mountain streams. By the mid 1780s, Merthyr had four major ironworks: at Cyfarthfa, Dowlais, Plymouth and Penydarren. “Penydarren was the perfect expression of a pattern of development common to all the Merthyr works,” says Professor Chris Evans in his book, The Labyrinth of Flames. Ironworks were established under the supervision of men who had learnt their trade in Cumbria or the Midlands, and funded from the profits of international trade. One of the key movers was Anthony Bacon from Bristol whose wealth was based on slavery, tobacco and molasses. His partner Richard Crawshay was a wealthy London merchant “whose interests stretched from Stockholm to Smyrna”. By the mid 1790s, Crawshay’s Cyfarthfa works was the largest ironworks in Britain. By the 1820s, Dowlais was the largest in the world.

Change happened rapidly. Specifically, Merthyr’s industrial prowess was founded on the sudden switch to coke-based technology — first to the smelting, then to the refining of iron coupled with Henry Cort’s “puddling” technique. The dizzying growth of Merthyr’s iron industry was fuelled by the exceptional coal seams on which the town rested. Limestone, used in the smelting process, was levered from the slopes of Cwm Taf Fechan.

After the Battle of Waterloo, the railway boom during the 1820s buoyed the demand for iron, but not for long. The slump of 1829 lead to the Court of Requests — bailiffs of the time — attempting to impound goods from the poor. As unrest grew, a sheet dipped in sheep’s blood became the first red flag of revolution to be raised in Wales. The Merthyr rising of 1831 had begun.

A century later, during the Great Depression, 80 per cent of the population faced long-term unemployment. Dowlais was dismantled and, although Merthyr’s fortunes revived during World War II, its heyday was history.

Prof Chris Evans’ talk on the Rise and Fall of Merthyr Tydfil at the Borough Theatre on February 20 starts at 7.30pm. Non-members are welcome to join on the night.

www.abergavennylocalhistorysociety.org.uk