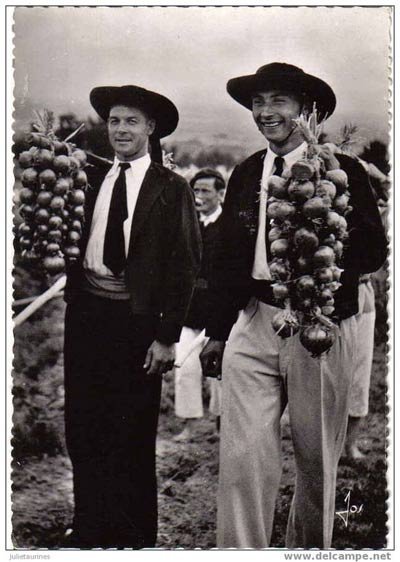

It is nearly 200 years since Shonis from Brittany started hawking their wares. Helen Morgan from Abergavenny Local History Society wonders why

It was 1828 when Henri Olivier, a Breton peasant, set sail from Roscoff for Plymouth with a boatload of onions. He sold them in next to no time and within a couple of days had arrived home with a pocket full of sovereigns. The news spread and thousands of Shonis (Johnnies) followed in his wake — driven by poverty in post-revolution France.

On this side of the Channel, a different kind of revolution was underway with men, women and children deserting the countryside for the mines, ironworks and mills. As a result food was often in short supply in the industrial valleys and ports. At one time the Shoni Winwns were a common sight from Land’s End to John O’Groats, especially in their heyday of 1919-1930. But nowhere were they more popular than with the people of Wales. “These were a Celtic people who shared a common ancestry and language dating from events in the immediate post-Roman period,” says Gwyn Griffiths whose talk on April 25 promises to be peppered with anecdotes gathered over the course of 30 years.

His early research began when he befriended Jean-Marie Cueff in Cardiff in the late 1970s. Cueff had begun selling strings of onions as a nine-year-old in Bryn Mawr in 1919. Like many Bretons, he spoke a few words of Welsh with a perfect accent, creating the impression that everyone in Brittany had fluent Welsh.

Before WW2, the Shonis had their ups and downs, including several shipwrecks in which many lives were lost. During the austerity years between the wars, the Ministry of Food was highly protective against food imports from anywhere except the Commonwealth. The Shonis’ salvation came when the autumn onion crop in Britain failed in 1946. Meanwhile, social conditions began to improve in France as well as Britain. By the 1970s, the younger generation could earn better pay (with pension provisions) in the factories, and most families did not want to migrate or be split up for months at a time.

Since then the Shonis have become scarce – although Philippe can still be seen at the entrance to Abergavenny market on Saturdays selling Normandy pate as well as onions and garlic from Brittany.

Gwyn Griffiths’s talk on the Shoni Winwns at the Borough Theatre on April 25 starts at 7.30. Doors open at 7pm. Non-members are welcome to join on the night.

abergavennylocalhistorysociety.btck.co.uk/ThisMonth